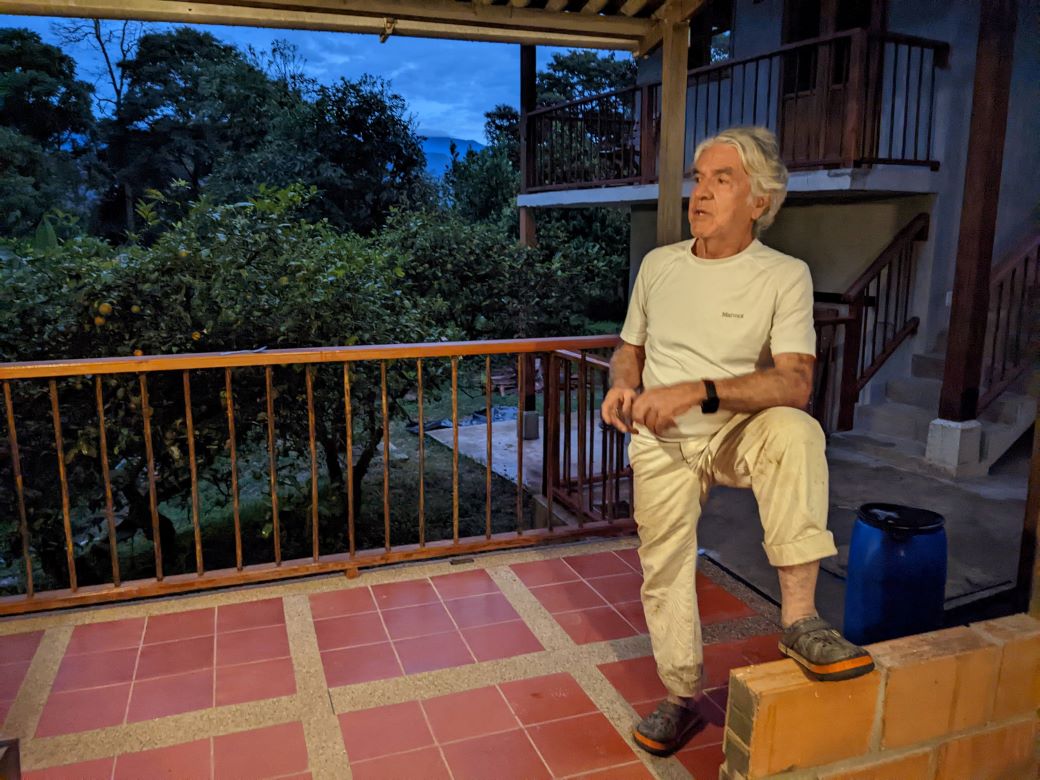

Don Alvaro Serna- slender, gray manes, cyclist, talkative- was born 71 years ago on a coffee plantation in the Eje cafetero, the famous coffee triangle between the Colombian cities of Cali, Medellin and Bogota. Tropical green hills, squeezed between the Cordilleras, the backbones of the Andes Mountains. Here it never gets hot or cold and the cloud cover is a given: it rains here more often than not.

Fine biotope for the coffee bushes that entered the Americas some two centuries ago, according to history in the wake of Dutch Jesuits. Don Alvaro squints and thinks back some sixty years. ‘My father grew coffee berries. We picked them on a heap and just sold the beans. My father did not drink coffee. No one drank coffee. We enjoyed drinking chocolate. ‘

Millions of coffee farmers in Central and South America grow coffee berries, but themselves drink little of it. You can buy a cup of passado, early in the morning in Peru, Ecuador, Colombia: usually a cup of hot water to which you add some coffee extract from a jug. In larger cities you do find trendy coffee shops with espressos and lattes for urbanites and tourists. For the Latinos themselves coffee is still mainly the cash crop that it has been for so long: growing coffee berries in exchange for a handful of money, with which you can buy the bare necessities, or send your children to school.

This exchange has never been entirely fair, pamphlets enough have been written about it. Multatuli wrote it down a century and a half ago in his Max Havelaar. Subtitles of more recent books like Black Gold; the dark history of coffee and Cofffeeland; one man’s dark empire and the making of our favorite drug suggest the same: coffee as exemplary of the dark side of capitalism; an unfair exchange with on the one hand a cheap cup of comfort, on the other exploitation, hunger and misery, that is the image of our cup of coffee.

But that image is changing. In the wake of Starbucks and encouraged by a growing army of artisanal coffee roasters, coffee farmers and customers have found each other in a niche market called specialty coffee; coffee that meets higher quality standards, in exchange for a price that sets the flywheel of progress in motion: better education, cleaner production, tastier coffee, even better prices. On a larger scale: less pollution and less migration.

Progress has not yet arrived everywhere. Drive into Peru from Ecuador, over the mountain ridge Cordillera: on both sides of the road steep slopes full of dark green coffee bushes. On the black, warm asphalt itself, drying coffee spread out on tarpaulins. The bus neatly slaloms around them, as it enters the town of San Ignacio. Se compra cafe, we buy coffee, is written on many facades.

Here coffee farmer Vilchez Tarrillo has thirty hectares, not a modest possession. But his son Mercedes prefers to maneuver his car through the endless rush hour of the Peruvian capital Lima, more than a thousand kilometers further south, where he has settled from the remote San Ignacio. ‘No, haha,’ Mercedes Tarillo laughs out loud, ‘I’m not going to take that over that farm, no way. That’s way too hard a life. And anyway far too far from civilization!’

Moonshining in Lima

Not that son Tarrillo doesn’t have a hard life in Lima either. Busy during the week as a paper representative, in the evenings and weekends as an uber driver moonlighting to make ends meet for his now broken up and scattered across million city Lima family. Still, anything is better than being a coffee farmer: ‘My father gets maybe 8 soles (€2) per kg for his coffee. There is no knowledge there, they just do something. They sprinkle expensive fertilizer, but eventually see the berries wither on the bush. What is needed there is knowledge. Agricultural experts.’

But in Chirinos -barely twenty kilometers from San Ignacio- those agricultural experts allready landed years ago. ‘Look’, says Luberrlly Tocto, a leaf from a coffee bush in his hand. ‘Do you see those reddish yellow spots, that’s coffee rust. I call it ‘my friend’, because he tells me I’m not taking good care of the plant.’

Luberrlly -third son of Finca Churupampa, twelve hectares of steep slopes, five thousand kilograms of coffee beans annually- climbs a bit further up the mountain, to show the solution: a covered compost factory where Tocto and his employees mix the fruit pulp of the coffee berry, a byproduct of the coffee bean – with other garden waste, animal manure and microorganisms, extracted from white clay higher up in the Cordillera.

Those organisms – no earthworms are visible – transform the piles into loose compost in four weeks. ‘We spread that around the coffee bushes, a few shovels each season. Initially the harvest decreased, but the soil recovered quickly. Now we have the same volume as with fertilizer, but a much higher quality.’

Special coffee

Coffee with a ‘cupping score’ of 80 or more (on a scale of 100) gets labelled specialty coffee. Specialty coffee yields highre prices and far better rewards for its producers. Ordinary coffee – also commodity coffee, bulk coffee, café convencional – is condemned to daily rates of the New York coffee exchange, which is ruled by speculation. Last year the market peaked and the best commodity coffee fetched up to $5 per kg, but the decline has already set in. There have been years the price never reached $2. Specialty coffee is much less affected by the coffee exchange. It starts this year at $6 per kg.

Specialty coffee is a product of what is called the ‘third wave’: in the 1990s, small coffee roasters from the US and Europe travelled south to collect coffee beans from coffee farmers in the tropics themselves. Luberrlly’s older brother Eber witnessed this focus twenty years ago, at cupping courses in Panama. ‘I saw farmers make such good coffees, I wanted to copy them here. I treid first within the local cooperative, but this didn’t work out. So we started ourselves, here at Finca Churupampa.’

Fertilizers, insecticides and herbicides gradually disappeared from the toolkit, compost factories, covered drying beds and test equipment arrived. The second year, seven neighbors joined, the next year thirty. In 2018, almost two hundred families already carried the brand Finca Churupampa, named after the Tocto family farm. ‘Last year four hundred families. In 2030 six hundred, we shouldn’t get any bigger,’ predicts Eber Tocto, whose little plan has grown into a veritable empire in ten years.

Pineapple between the coffee

The fincas -plantations- of affiliated coffee families are located in all directions from the coffee town of Chirinos. Half an hour over gravel roads westwards, Cleber Acosta is considered an example farmer within Churupampa.

His intensely green slopes are as steep as all the others in Peru, but show more space, the coffee bushes more vital. ‘I plant them further apart, so plants don’t compete with each other, otherwise you have to use fertilizer again. I may have lower volumes now, but better coffee’s.’ In the gained space Acosta plants trees and crops that you can eat or sell and that go well with Coffea arabica, such as pineapples. ‘Pineapple works well against black foot rot, a fungus.’

Ten years ago -coffee prices fell again- the future looked very different, Acosta recalls. ‘I was about to uproot all my coffee for other crops, until Eber asked me: Do you have land? Yes I said, but the coffee isn’t worth it. It is, if you specialize, Eber said.’

Perfect coffee

Model farmer Acosta now even has his own coffee lab: roaster, coffee grinder, the prescribed cups, in his shed packed with large coffee bags. There he can always taste what he makes himself, or receive buyers. Today, buyer René Padilla Quiroz is sipping Acosta’s latest Geisha, a delicate arabica variety. ‘Geisha, delicious coffee. I am impressed.’

Mexican Quiroz is one of the army of hip, free-spirited and adventurous sourcers who search for quality coffees, vividly portrayed in yet another book about the third wave in coffee: God in a Cup: The Obsessive Quest for the Perfect Coffee.

Reciprocity is essential among sourcers: they come to collect coffee beans, in return for a sustainable price and more knowledge, so the farmer can keep supplying coffee. For example, things can go terribly wrong during the fermentation of the coffee cherry into coffee bean, with major consequences for the taste. Quiroz: ‘And we teach him what the market wants. For example this Geisha, which sells well: we supplied Eber with the seeds ourselves, now he supplies us with coffee beans in return.’

Sourcing never stops. A further quarter of an hour over gravel roads, Quiroz is looking for new quality coffees from coffee farmer Wilder Falcando. In Falcando’s wake a line of children and pregnant wife. Falcando shows the plantation, the bassins in which he pulps his coffee cherries and processes them into beans. The covered drying beds, where molds have no chance, all learned within Churupampa.

That knowledge came just in time. ‘I saw my father work so hard, I thought: as soon as I can afford it I’m off to live in the city. Until I came into contact with Churupampa. I work just as hard as my father, but now it pays off for me,’ says Wilder, his eyes tensely focused on Quiroz, who is attentively drinking his latest coffee.

Social empire

This year, Churupampa pays affiliated growers at least three hundred dollars for a quintale, a 55kg coffee bean bag that meets basic requirements: a score around 83. If a farmer cultivates and processes carefully, that is quite achievable. Eber Tocto calculates roughly: ‘That’s one hundred and eighty to cover the costs of the grower, fifteen for transport, two for our profit. Leaves around a hundred dollars profit per bag for the farmer. Or more, if his coffee scores higher than 85.’

Eber Tocto himself has meanwhile moved out of the mountains into the city of Jaen, at the foot of the mountains. To better oversee selection, processing and transport, he lives behind the warehouse where workers carry sacks of coffee on their shoulders into containers, on their way to coffee lovers around the world. The ‘social’ enterprise Churupampa today has thirty permanent employees and a lot of freelancers. For example, six agronomic advisors walk the coffee plantations.

At the original Churupampa farm in Chirinos, the brothers have built a bar and swimming pool, for parties with affiliated coffee farmers and an unmistakable message. Eber Tocto: ‘To show everyone that you don’t necessarily have to migrate to the city for progress. That you can perhaps achieve that better life more easily right here.’

Disrupters

The Peruvians still have to sell their coffees on the other side of the oceans. In the long chain between coffee cherry and cup of coffee, middlemen have a notoriously bad reputation; coffee is traded so often, sometimes only a fraction of the kilo price ends up with the farmer.

In a rudimentary office above a coffee roasters collective in Amsterdam Noord, Lennart Clerkx explains how he himself became the middleman he actually wanted to eliminate. ”Solving logistics, cutting out intermediaries. That didn’t work out, so I just became an importer myself. A transit hatch, that’s ThisSideUp.”

ThisSideUp calls itself ‘the good middleman’ that bundles coffee from small farmer cooperatives and connects it to small roasters. Small coffee roasters buy their green coffee beans there, from all tropical latitudes. Their website lists which farmer grew the beans, whether they taste like nuts or fruit, what the cup scores are. Next to it in a pie chart what the farmer gets, what transportation costs and what share the good middleman himself takes.

Clerkx and co-owner Maarten van Keulen call themselves ‘disrupters’, they want to push the coffee market in the right direction. They don’t do with certificates, but with short, traceable lines, as good intentions may also go awry. Clerkx: ‘In those cases we want to arrange things with farmers we know, whom we can look in the eye.’ Van Keulen: ‘We present a new system, one that replaces the existing system. Everything transparent and based on trust. With the philosophy you can be kind to each other, to the environment and still make money.’

ThisSideUp has grown spectacularly in recent years, from five bags in 2013 to twenty-five containers last year. Van Keulen: ‘That makes fifty million cups of coffee. Not bad for a niche market that is said not to be scalable.’

Illusion

Not everyone agrees. Sofie Nys of the Antwerp coffee importer Sucafina adds a footnote: the specialty market relies too much on super coffees. This way you cannot save the world, says Nys. ‘Only the small top segment of the production of a plantation can be specialty. Micro roasteries in Europe buy those high qualities at high prices, but claiming specialty coffee is the sustainable savior of the industry with such a small volume, is rather an illusion.’

According to Nys, it would be better to focus on less special specialty. Specialty coffees of 84 are easier to make, also by farmers who own land where you never get that 87. ‘Not everyone has the ability to jump on the specialty cart, due to limited coffee production, other priorities, lack of support.’

Lower scoring coffees can significantly boost the total specialty volume. ‘When specialty is traded on a large scale, this niche market can support sustainability claims. Not so much through the highest qualities that are impossible for many producers to achieve and that now get a lot of attention from small roasteries.’

Whether self-proclaimed disruptors like Van Keulen and Clerkx can make specialty mainstream will become clear in the coming years. Importer Sofie Nys sees demand for specialty increasing, but notes that not everyone has a realistic price for it. ‘We already got requests for unroasted traceable specialty for less than €4 per kilogram. Then I ask the counter question why they want traceability, while paying the producer below the price of production and shipping.’

Coffee goes through many hands, which makes tracing complicated. Hands that each time add value to the product and are often rewarded too low, but sometimes also exorbitantly high. Tracing can therefore also be undesirable. Add to that a few strokes of marketing and you get a coffee market that teems with unverifiable claims like sustainable and fair. Van Keulen has one tip for the consumer: ‘Unleash the critical consumer in yourself. Look at roast date. At origin. The more detailed, the better.’

Top coffees from Colombia

Crossing the Atlantic Ocean again, Ronald de Hommel tries to make himself heard over the clatter of yet another tropical downpour, on the roof of his huge coffee warehouse in Rionegro, not far from Medellin, Colombia. De Hommel – previously a photographer – started with a few bags of coffee a decade ago, when he found love and settled in Colombia. ‘Because in the traditional coffee industry everyone earns except the farmer himself, I wanted to eliminate that middleman. With a webshop, a coffee roaster in the Netherlands and nothing else. That turned out to be too idealistic.’

Fifteen years later, more than two dozen employees of De Hommel’s umbrella company Coffee Quest – ‘specialty coffee with added value’ – ship around thirty containers of green quality coffee around the world annually.

Wilson Ordonez, a fifth generation coffee farmer, annually supplies De Hommel with six thousand kilograms of top coffees from San Agustin, in the province of Huila in southern Colombia. Thanks to Coffee Quest’s prices, Ordonez is doing well, but he sees his younger colleagues around him actually leaving commodity coffee: ‘It’s working from six in the morning to eight in the evening. The costs are high, the profits low, there is little left over. That’s something younger people don’t feel like doing anymore.’

Take Eric Fernando Bravo, he left San Agustin for Bogotá when he was eighteen. Only to retrace his steps at the age of twenty-four, to setlle back at Finca Chaferote, his family’s plantation. You can only get there on foot, via a slippery path that leads to the Rio Magdalena, the river that cuts through Colombia and flows into the Caribbean 1500 km further. Bravo: ‘Working in a clothing factory in Bogota wasn’t everything either. My family is here, there is light and air here’.

Eric Bravo leads the way to Chaperotte. Last kilometer is downhill and only on foot. Coffee goes back uphill by donkey

On the slopes above, Bravo has been working to rebrand his coffee for six years now. With the help of Ordonez and Coffee Quest, Bravo and his father converted their plantation to specialty coffee. The five thousand kilograms annually now provide enough cash to feed nine people, supplemented with crops like corn, yucca and bananas that grow between the coffee, and the chickens that scurry around below.

Bravo does not yet grow his coffee completely without fertilizers. Sometimes the chemicals still have to combat a disease. But everything is being phased out, with the consent of importer Ronald de Hommel, who gets annoyed by growing influence of certificates and certifiers. ‘Give those farmers some room, help them make the switch. With trust you get much further, otherwise they will hide everything when the inspector comes.’

Green Deal

The European deforestation law will impose even more rules on coffee farmers. From 2024 onwards, agricultural products for which forests were felled may no longer be traded. ‘11% of global CO2 emissions come from deforestation,’ explains Gert Van der Bijl. For NGO Solidaridad he visits European coffee importers to explain the law. ‘10% of those emissions come from EU imports, of which 9% is coffee. Our coffee imports contribute about 0.1% to climate change. It may sounds superficial, but is in fact significant.’

In conventional coffee cultivation, it is difficult to prove that no forest was cleared, says Van der Bijl. By linking the exact origin to satellite images, this can be done. ‘But in Indonesia, for example, there is so much intermediary trade that guaranteeing coffee is deforestation-free becomes difficult.’

This problem applies less to specialty coffee. Importer Van Keulen says he has long been ready for the anti-deforestation law. ‘We know exactly from whom we bought coffee. Bulk buyers have a problem. This forces the entire industry into traceability: where does the coffee come from? And are they paid well? They are being forced in our direction.’

Van der Bijl confirms that specialty coffee models work better. ‘There is no guarantee, but there is a correlation. It is based on long-term collaboration in a sector that feels responsible for the well-being of its suppliers.’

Sergio Londoño shows the little frog of Asocafe Tatama: ‘Because it stays alive if you grow coffee cleanly.’

Rainforest frogs and fair trade stamps

Besides rules from governmental bodies like the EU, certifiers such as Fairtrade and Rainforest Alliance have for decades been trying to make the coffee industry fairer and cleaner. In the specialty coffee world, their green-blue stamps and frog symbols on the coffee packs are frowned upon and mainly seen as a marketing tool.

Importer Van Keulen classifies them as greenwashing. ‘They only cut the sharp edges of the neocolonial system. The question is whether the coffee farmer is really better off with it. We prefer linking quality to better prices: we want to pay you better. If you do this and that, we can also sell it.’

Importer De Hommel even gets ‘dead sick’ from it. ‘You pay a quarter more for your coffee, of which twenty cents goes to those certifications and five cents to that farmer, if it gets there at all.’

When asked, Michelle Deugd of Rainforest International specifies the amounts. ‘Buyers pay an average premium of sixteen dollar cents per kilogram – it can be ten cents, but also much more- on top of the market price. Another three dollar cents are for us, Rainforest Alliance. With that we pay for training, research, communication and advocacy for all those farmers.’

According to Deugd, Rainforest Alliance attaches great importance to traceability within the supply chain. ‘When companies buy certified coffee, we impose strict requirements to be able to track the route of the coffee.’

But Rainforest Alliance does not check itself whether farmers and traders adhere to them. For this, individual farmers or their cooperatives must hire certification bodies and also pay for those audits themselves. Whether and how often this happens and who controls the controllers themselves has very little visibility.

Nespresso and Starbucks

According to De Hommel, only the link with quality can save coffee cultivation. To illustrate he refers to large-scale buyers like Nespresso and Starbucks, whos influence is many times greater than that of certifications, even though they still ‘pay far too little’. ‘They do pay a little more than that quarter, so farmers are happy. But when you see how incredibly many millions Nespresso and Starbucks earn, they still pay their farmers ridiculously little.’

And yet it was Nespresso and Starbucks who gave coffee cultivation a nudge in the right direction, says De Hommel, by starting that Third Wave. ‘Because of Starbucks all those coffee bars arose where you can get much better coffee than at Starbucks itself. They feel our hot breath down their necks. If we can get those commodity traders up a few more steps, that’s a win for the farmers. And for us. Otherwise, in two generations no one will want to work in coffee anymore.’

Back to Don Alvaro from the first paragraph of this story. Alvaro left the coffee plantation, became a chemist, traveled north, married an American woman and had American children.

Somewhere in the late last century, Alvaro nevertheless bought an abandoned coffee plantation in Circasia, Colombia, for the holidays and for after his retirement. Six years ago, daughter Angela also did not return from vacation to her well-paid architect’s job in the US.

Now she devotes herself with a mix of dedication and perseverance to the cultivation of specialty coffee, which finds its way to nearby and faraway customers a little better every year. ‘We decided to produce less, but better coffee, between our own food and the fruit that already grows there. It’s a long way to go. There is little knowledge and little help, no formula and no book.’

Angela wants to add a last word, just before we return to Europe after three months along countless coffee farmers in Peru, Ecuador and Colombia, ‘The best thing is if they can find my coffee in your store. My coffee doesn’t have to be more expensive, because I don’t have all those middlemen.’

Characteristic Colombian Willy jeep with a grand total of twenty-six passengers, on the mountain road between the coffee villages of Santuario and Apia

This article was translated by AI and previously appeared in Dutch on Vrij Nederland and in Flemish on Mo.Be