Manaus, October 2022

Together with Alberto César Araújo, photographer and co-founder of the internationally awarded journalistic website Amazônia Real, we drive to the grounds of the Cemitério Nossa Senhora Aparecida on the Avenida do Turismo in the Tarumã district of the Brazilian Amazon city of Manaus. Cemitério Nossa Senhora Aparecida is a public cemetery. People do not have to pay for a family member’s grave here. Next to it is the private cemetery Cemitério Parque Tarumã. We get out of the car. The heat hits us hard. To the left and right, in front and behind, everywhere around us are large plots with long rows of closely spaced graves, most of them marked by a wooden cross made of two slats. On it, written in black marker: a name, a date of birth and death, and the number that identifies the grave’s location as a cemetery ID.

The cemetery is quiet. The graves are in a state of desolation. Few care for the resting place of a deceased loved one. There’s little left to care for. The elements, the heavy rains and the great droughts that the area has suffered, have destroyed much. In various places, broken crosses lie on the ground, cracked and crumbled by the drought, and the wooden markers have disappeared. Here lie the poor of Manaus, whose remains will soon not only be washed away, but their names will also be erased.

Covid-19

Suddenly, like a block of concrete on a highway, there was Covid-19. The pandemic raged through the Amazon like a devastating storm. Images of mass graves were sent around the world. In cemeteries, shovels dug trenches to hold the many coffins of the dead. People said goodbye to loved ones, lost jobs and income, and were thrown back on themselves. As elsewhere in the world, physical contact was kept to a minimum.

Manaus was one of the epicenters of Covid-19 in Brazil, with streets filled with refrigerated containers to store bodies, mass burials, and a severe lack of oxygen.

The virus hit the city hard. A huge disaster was unfolding. I was communicating digitally with my friends. Their messages spoke of collapsing health systems, genocide of indigenous tribes, increasing deforestation of the Amazon, and on top of the rubble, a crazy president (Bolsonaro) and his gang. Manaus was in chaos.

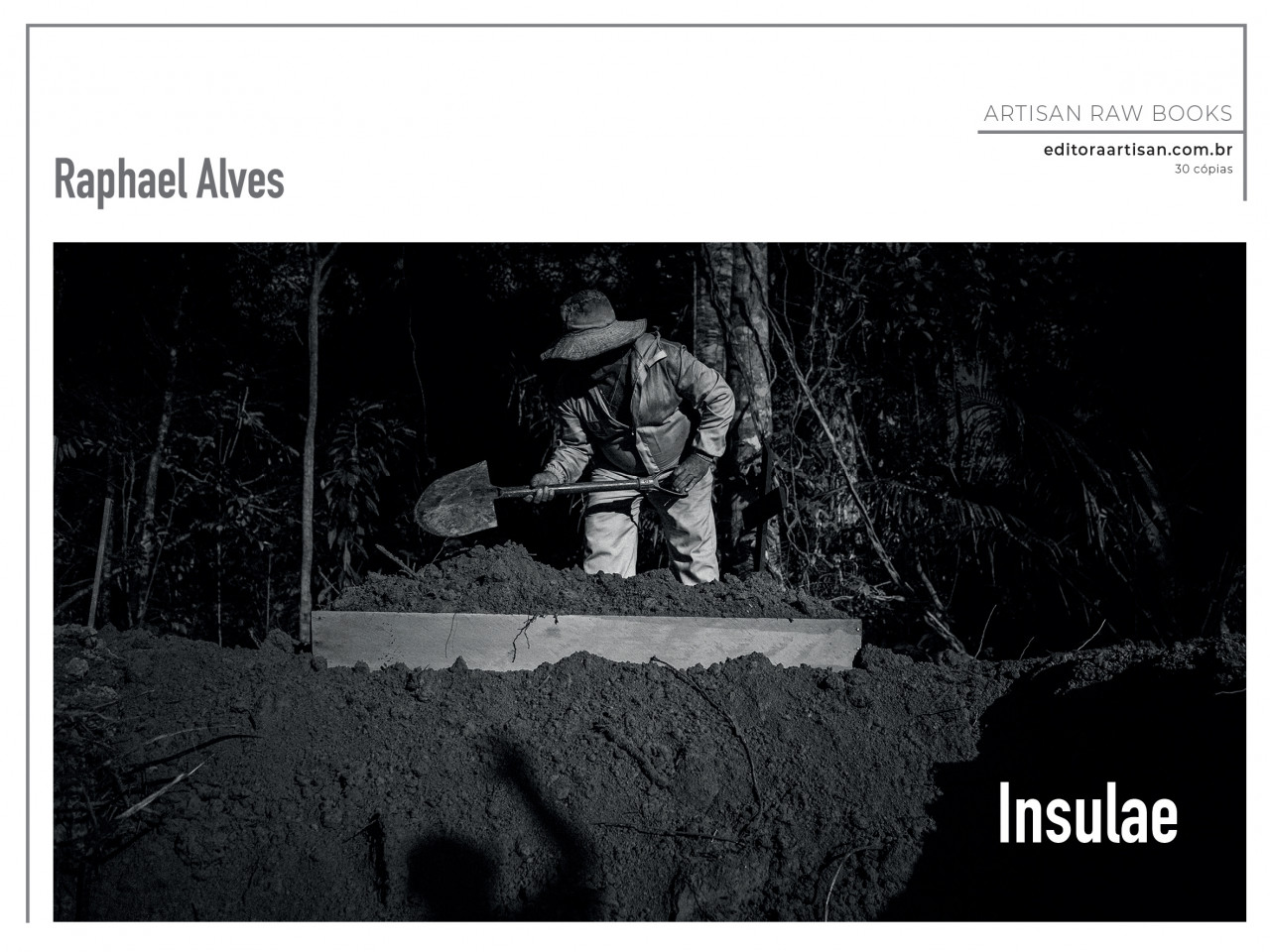

The shadow of a person attending the funeral of a victim of Covid-19 is projected on a collective grave as a funeral director closes the grave under a harsh sun at the Nossa Senhora Aparecida cemetery, in the western zone of Manaus, on June 5, 2020.

“Everything is collapsing. People are dying, breaking their isolation, hospitals are running out of beds, corpses are stored in refrigerated containers, and the city government keeps building new cemeteries…”. This is how my friend and photographer Raphael Alves described the situation in April 2020. Raphael Alves photographed the Covid-19 pandemic and its impact on life in his hometown of Manaus from the day of the first registered infection in the Amazon city: March 13, 2020. He was there when the situation at the João Lúcio Hospital in Manaus spiraled out of control. It was internationally reported (and confirmed by the local government) that beds with deceased patients were next to beds with infected patients fighting for their lives.

The photographer published a limited-edition booklet, Insulae, about the Covid-19 pandemic in Manaus and the Brazilian state of Amazonas. He wrote in the foreword:

“The insulae – from the Latin that led to the word ‘isolamento’ in Portuguese – were forms of housing for the most disadvantaged people in ancient Rome. These buildings, whose construction was so fragile that they could easily collapse, housed thousands of people in unsanitary and dangerous conditions. Without sanitation, crowded together and isolated, the people in the insulae had no way out.

The problems of the Amazon have long created situations on the verge of collapse. But it was a new emergency – the Covid-19 pandemic – that highlighted socio-economic inequalities and the general lack of policies as one of the most glaring social negligences in the region, underscoring the fragile structure of the largest state in the federation. The distances and transportation difficulties, the absence of normal and very complex health services in the interior, the lack of water and a minimally qualified sanitation system – a situation that continues during an outbreak where the most basic form of prevention is the act of washing hands – are directly reflected in an unprecedented health crisis.

Families are being torn apart, indigenous peoples and their cultures are under constant threat, people are dying in their homes without the slightest chance of help, there are collective burials in mass graves, victims of the disease are piled up in refrigerated containers next to hospitals. These images (in Insulae – CCE) represent and at the same time show only a part of an even more complex reality.

There was no way out for decades of misplaced priorities. The bill came due, and like the Insulae, the Amazon collapsed. Pandemic and neglect have taken a heavy toll: lives. Thousands of them are now buried in the isolated Amazon region.”

Photographer Alberto César Araújo called the situation “hell”. And a friend in Manaus, who was herself infected and had to say goodbye to her mother during the pandemic, wrote:

“Every day there were more than two hundred deaths due to complications from lack of care in overcrowded hospitals. MANY DOCTORS recorded videos announcing that they had to choose who would live and who would die in overcrowded wards without adequate equipment. Cases were reported of elderly people being placed in body bags while still breathing. Refrigerated containers were placed outside hospital entrances to receive the dead of all ages. People were given the bodies of others to bury as if they were their own family members. The dead were placed on the outskirts of town next to the hospital, where there was no refrigeration, exposed to the sun. Seriously ill patients, unable to breathe on their own and dependent on oxygen for treatment, were given morphine to ease the pain and died slowly. Scenes of war hospitals only seen in movies took place here.”

Manaus Moderna, October 2022

In 2013, I was the field producer (fixer) for the Amazon episode of the Dutch IKON TV program ‘Paul Rosenmöller and the struggle of Latin America’, together with photographer Raphael Alves. The opening images of the documentary show the chaotic port area of Manaus, the gateway to the city. This is the place in Manaus that I always go to first. I know the people there, and they know me: porters, skippers and fishmongers, the homeless, beautiful freaks and alcoholics.

Although it is called ‘Manaus Moderna’, it is a very neglected district. Politicians rarely show up there outside of election time. The neighborhood is considered ‘dangerous’.

For more than twenty years I have been coming to Manaus Moderna, but in all these visits I have not seen any improvement in the living conditions. Manaus ‘abandonada’ is written on a wall. The people there feel abandoned.

During my wanderings in the area, I got to know many of the residents, sometimes bandaging a wound, sometimes buying ingredients at the market to make fish soup on the spot, over a fire on the waterfront.

After an absence of three and a half years, I am back in the Amazon, in Manaus Moderna. The great activity of the past is missing. The place looks even more dilapidated than the last time I was here. One of the metal stairs to the river is broken in half and hangs there like a surreal sculpture. The same goes for one of the floating docks, which, overwhelmed by the bow wave of a passing ship, lies distressed on the riverbank like a gigantic, gasping fish.

Many people I knew in Manaus Moderna are missing, especially the elderly. They have retired, I hope. But many have died or are bedridden with illness, according to the few who are still there. The young porters who now work in the port, carrying loads up and down the stairs, and whom I do not know, mostly speak Spanish. They come from Venezuela, as do the mostly indigenous refugees who try to make a living in Manaus by begging, most of them women with children.

As I said, Manaus has been hit hard by Covid-19 in recent years. Many still remember the television images of people desperately searching for oxygen for their sick family members, the online pleas for help from health workers, the photos of mass graves. I also lost friends and acquaintances in Manaus to the pandemic. Among them was Zezinho Corrêa, the Amazonian singer and actor who had a worldwide hit with his band Carrapicho in 1996 with the song Tic, Tic, Tac*.

I vividly remember Zezinho’s performance on the day of the final match of the 2014 FIFA World Cup Brazil, when we could celebrate life freely and global pandemics only existed in science fiction stories or movies.

Manaus, Sunday, July 14, 2014

The 2014 FIFA World Cup is over. Germany won, Brazil lost.

After the final, Carrapicho performed in the Largo de São Sebastião in the World Cup host city of Manaus. Singer Zezinho Corrêa once again emphasized the riches that Brazil has to offer the world, such as music, dance, gastronomy and, above all, an impressive nature. The Atlantic Rainforest, the Cerrado, the Pantanal and the Amazon are areas that must be cherished for their biodiversity, their natural wealth and their contribution to a world worth living in for future generations.

A wave of enthusiasm swept over the Largo de São Sebastião in Manaus as Zezinho closed the show with an impressive rendition of the Brazilian national anthem, including the line “Nossos bosques têm mais vida” – “Our forests have more life”.

Back to the present. Cultural life in Largo de São Sebastião, where the legendary Teatro Amazonas is located, is as vibrant as ever. A few still wear masks, but in general the people who gather here in the evenings with family and friends, filling the terraces and enjoying the free live shows and concerts, prefer to forget the Covid-19 disaster that swept through the city. Not forgotten, however, is Zezinho Corrêa. He looks at me from huge murals. He was an important artist and musician who did a lot for the city, say the two Jehovah’s Witnesses who, under the watchful eye of Zezinho, or Zé as his friends called him, promote a free Bible course on the street.

When I think of Zezinho, but also of those who lie side by side in the cemeteries and whose names will soon be washed away and forgotten by time, I hope that the Brazilian people will send their opportunistic and visionless politicians home and that a truly sustainable future can be built, for them and for us. The clock is ticking. Tic, Tic, Tac.

“Bate forte o tambor, galera!” – “Beat the drum, everyone!”

*Tic, Tic Tac by the Brazilian band Carrapicho was released in June 1996 as the lead single from the album Festa do boi bumba. The song was also recorded by Chilli featuring Carrapicho and released in May 1997. The original version reached the charts in Belgium, France, the Netherlands and Spain. The remix version, produced by Frank Farian, entered the charts in Austria, Canada, Germany, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.