For the time being, she is the only source who published this message on her Facebook page. Let’s assume that this is indeed true. Then a sad picture emerges of a man who died in complete anonymity and loneliness at the age of 80. It is perhaps understandable that no significant media has paid attention to his death. His last record dates back to 1994. Apart from performances in local bars in Nashville, he has not been part of the music industry for years. No manager, no record company that supports you, well, then you apparently disappear from sight of everything and everyone. A few weeks after Kuhn’s message, the administrator of his website confirms his death, although a cause of death is not mentioned.

“There’s only one countrysinger who has influenced me and that’s Lee Clayton”, claims U2 singer Bono. In the late eighties Bono, U2 bassplayer Adam Clayton (no relation) and their idol meet in Nashville. They spend a few days together. “Really nice guys,” Lee says afterwards to Jip Golsteijn of the Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf. No doubt that Naked Child also must have been Bono’s first introduction to Clayton. After all, it is the album with which the countryrock singer made his name in Europe around 1980. He even receives the Edison music award in the Netherlands.

From the jury report we read: “Lee Clayton has succeeded in pushing the boundaries of this category with the lp Naked Child. His clear language, solid instrumental approach and strong compositions in which unmistakable blues and rock influences occur, provide one of the highlights in a genre that has been in a state of flux in recent years”. During the same Edison edition, Stevie Wonder and Charles Aznavour also receive a statue. Lee Clayton’s name seems definitively established.

But he is also headstrong and unpredictable. When his marriage falls apart in 1967, he decides to train as an air force pilot with the US Army. “One morning, coming out of the pub, I was stuck in a traffic jam when a plane skimmed dangerously low over the highway. It turned out to make an emergency landing, but I thought: I want that too! I loved my wife, but she studied math night and day, and within a year we were divorced and I was in the Air Force.”

And there he goes, Billy Hugh Shotts as he is actually called, flying through the sound barrier of the California airspace in his F-101 Voodoo jet fighter. He almost dies when he spins at 1500 feet and manages to straighten his plane just in time. During his service time he also learns about the use of cocaine and alcohol. Subjects that recur frequently in his lyrics, which are strongly autobiographical anyway. He writes about his adventures as a pilot (Old Number Nine) and about his drinking and drug use. The songtitle Tequila Is Addictive says it all.

But Billy the army pilot feels in every fiber of his body that he is above all Lee Clayton the songwriter. One of his songs, Ladies Love Outlaws, is covered by Waylon Jennings and the Everly Brothers. It provides him with a source of income, so that he no longer has to spend the night in his car or pick up ladies in local bars for a place to sleep. Many years later, more of his songs are reworked by artists such as Willie Nelson, Sturgill Simpson, Bill Callahan, Cat Power and in 1982 even by Dutch weirdo’s Dizzy Man’s Band (Oh, How Lucky I Am).

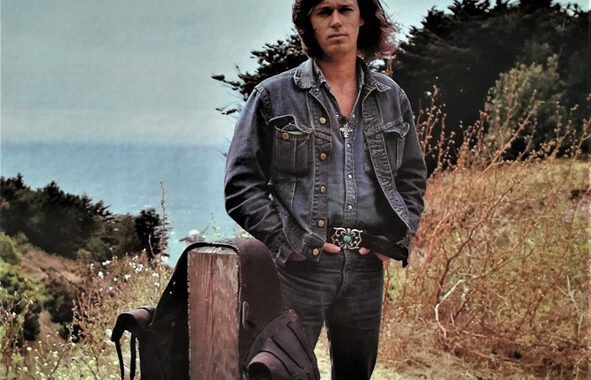

Lee Clayton then befriends two other country music outlaws, John Prine and Kris Kristofferson. Eventually he is offered a record deal. His debut, released in 1973, contains a large number of truly beautiful songs. What immediately stands out is his warm melancholic lamentation. When Lee Clayton starts singing, everyone suddenly falls silent. The record company is doing everything it can to make the album a success. A variety of studio musicians are hired. Carly Simon can be heard in the moving New York Suite 409. It doesn’t help much. The record doesn’t get any attention and barely sells. A countryrock classic is nipped in the bud. On the cover the singer looks stoic and a little surprised, wearing a denim jacket, belt half loose, hands in his pockets.

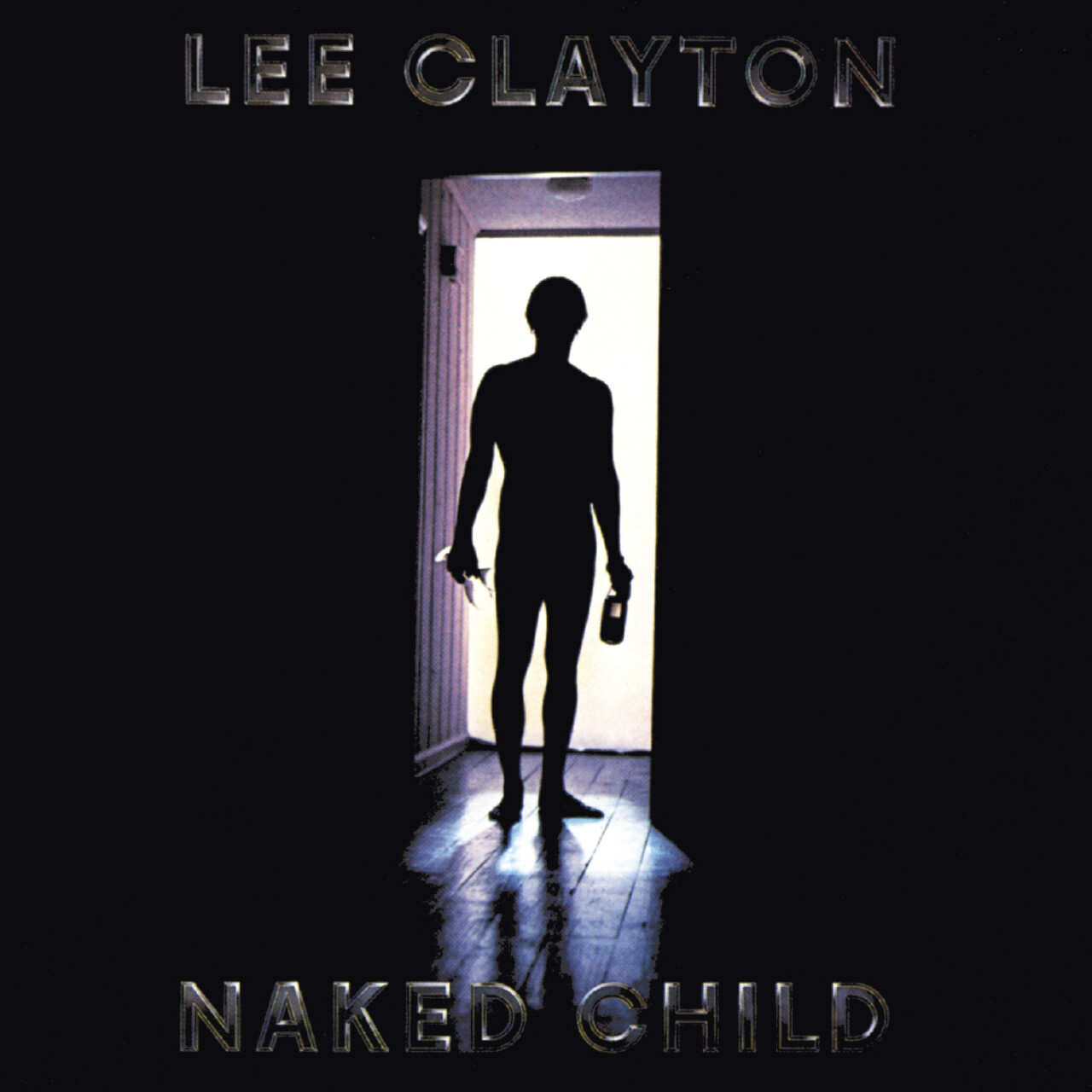

Clayton receives his Edison for the country music category. However, Naked Child contains absolutely no music you normally associate with Nashville. Between the new wave and postpunk of that time, this record stands out, a record that cannot be compared to anything else. During the recording of the album, a disagreement arises between Clayton and the producer. Out of sheer frustration the singer secretly decides to steal the tapes from the studio. He even keeps them under his bed for a while. Only after long negotiations with the record company he hands over the recording tapes.

A few songs turn out to be so gripping for the musicians (including J.J. Cale and bassplayer Klaus Voormann) they’re only able to perform them in one take. These versions can be heard on the record. The lyrics are extremely personal. Clayton is not shy about his despair, loneliness and disappointments. About his lack of love, about the women who reject him. The singer stands naked with a bottle of liquor in the light of a doorway. The frame around the doorway is pitch black.

“It’s true I’m not much on talking

It’s true there’s not much I know

But one thing I’ve learned for certain

You reap whatever you sow

And you ride, you ride alone

Yes you ride, you ride alone”

from I Ride Alone

This is a heartfelt cry from a man who resigns himself to his existence as a loner, doesn’t belong anywhere, understands that you have to bend in order not to burst, and tries to find peace with that realization. That’s what Naked Child sounds like. There are thunder-and-lightning solo’s by the various guitarplayers, and of course there is that voice, which deeply hurts despite its emotional sincerity. A record that takes you to places that are different from the places you already know. A record like a desolate ghost town from the old West. Lee Clayton has definitely made his classic album.

But it seems as if he is so impressed that he himself seems a little frightened. The admiration and fame he gets with the album visibly fades away when he doesn’t make much of himself after that. Successor The Dream Goes On is weighed down by a typical eighties sound. Sales are disappointing. Clayton loses his record deal. Years of silence follow. He spends his time doing nothing. In the life of the former countryrocker who has seen it all, this means staring at the ceiling, restless, without inner peace, according to his own words.

Around 1990 there is a small revival around his person thanks to a renewed interest. But Lee Clayton has then become a cult figure admired by only a handful of enthusiasts. A few years later, he releases a new album, unfortunately a very disappointing one. Noteworthy however is The Streets Of Nashville – The Little Book. In addition to his lyrics and poems, the modest-looking booklet of barely eighty pages, contains self-reflections and anecdotes about the hard life of a musician.

For example: once after a performance he does not receive the wages in money but in narcotic pills. That he is offered a room in a boarding house paid for by the notorious singer Billy Joe Shaver. That he witnesses how the same Shaver knocks an annoying visitor to the ground with one punch in a bar. Clayton bluntly describes life on the road, overcoming countless setbacks, suddenly emerging annoyances about his touring musicians, but also about his love of songwriting that has kept him going all along.

In 2017 out of the blue sounds a very last impassioned plea. Lee Clayton’s ever last recording. He sings with a broken voice. Let Love Live In Me.