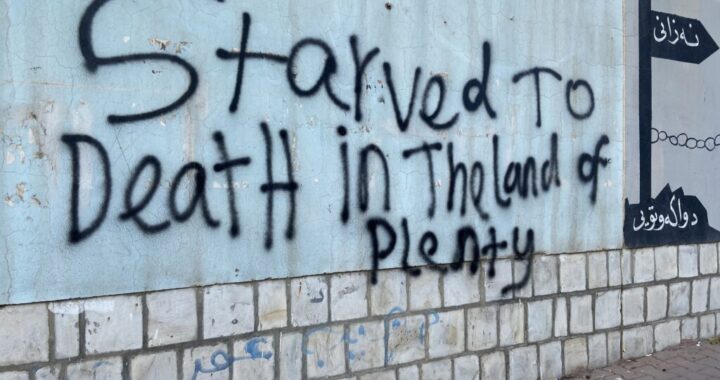

“Starved to death in the land of plenty” is written in large letters on a wall in Sulaymaniya. The cultural heart of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq is where I settled fifteen years ago, to contribute to the development of democracy in post-Saddam Hussein Iraq.

A city that was then in development, like the rest of Kurdistan. With a real economic boom in the years that followed, and a growth of as much as ten percent. The trees seemed to touch the sky. Freedoms were also on the rise. New newspapers and TV stations emerged. The media center I had set up could barely meet the demand for journalism courses.

A new political party named Change (Goran) was founded. But at the same time, for most Kurds, life never was so good. Larger houses, sometimes with two cars parked in front. The very first supermarkets, that even sold European products. Improved infrastructure, new highways. And increasingly more flights from the two Kurdish airports.

Yet things were far from flawless. One of my students was murdered in 2008 for investigating the relationship between prostitution and politicians. In 2011, there were weeks of protests in Sulaymaniya after an initial demonstration for political renewal ended in violence with fatalities. And when the new Change Party was involved in the government, it mainly led to conflicts and even the expulsion of its politicians from the capital city Erbil.

Pendulum

You, Mr. President, were the Prime Minister at the time, with a few years’ break when Barham Salih took over. And I am still grateful for your support for the Media bo Khalk (Media for the People) training program, which enabled graduates to enter journalism. Many of them have done quite well.

But those years of growth and relative political stability seem far behind us now. The pendulum of democracy and prosperity has swung the other way. Journalists in Kurdistan who criticized the government are imprisoned without a fair trial. Foreign journalists have been expelled. Jewish travelers, once so welcome, have been turned away at Erbil airport.

Rockets are falling on members of the Kurdish opposition from neighboring Iran, who are your guests. Turkish drones are attacking Turkish-Kurdish opposition members who sought refuge with you. Foreign troops at Erbil airport, who came to assist you in the fight against ISIS, are also being targeted.

The stability that existed for many years is gone. Public servants have not received salaries for months because Baghdad is not sending the money. Agreements that your cousin, the Prime Minister, made under great pressure—sending oil revenues to Baghdad in exchange for a slice of the Iraqi budget—are not being honored. Meanwhile, oil exports to Turkey have been halted for months because the Turks see more advantage in a divide-and-rule strategy than in the revenue they would also benefit from.

Mood

The mood among Arab Iraqis regarding the Kurds has turned. Over one-third (38%) now want the region to lose its special status within Iraq. More than eighty percent believe that the Kurds have no right to their own oil. Only thirteen percent still think that there are more freedoms in Kurdistan than in the rest of Iraq.

Why? Because the conclusion can now be that the ‘Other Iraq,’ the nickname that Kurdistan chose to market itself for tourism, is no longer so different from the rest of the country. It’s a warning you can’t ignore, one that should force Kurdish politicians to face their responsibilities.

Where it started to go wrong was with the arrival of the radical group ISIS. They were barely stopped at the border of Kurdistan but still kidnapped and killed thousands of Yazidis. It was the arrogance following the successful war against ISIS that has brought the Kurds to where they are now. The arrogance that led to a referendum on independence, which ended much of the goodwill that had been built up and gave old enemies a chance to trip up the Kurds.

Although most parties eventually participated in the referendum, many within the second-largest party, PUK, felt forced to do so. They realized the timing was wrong and heeded outside advice. And they were quick to blame the initiators from the KDP for the damaging effects.

Together

History has shown that the Kurds are only strong when united. And yet it happens time and again: whether manipulated from outside or not, that unity gets lost. The last time the division was so big, in the 1990s, it led to a civil war. Now, it mainly leads to hardship among the population, and enemies from across regional and national borders who are increasingly turning up the pressure. And we both know: under pressure, everything becomes fluid.

So much so that under pressure from Iran, Iranian-Kurdish opposition groups have been forced to abandon their bases in the mountains on the border and leave. Lethal attacks on members of the Turkish-Kurdish PKK have been permitted, even though they also hit others. Not all units will participate in the evacuation, and the PKK has warned to leave their territory alone.

You speak reassuring words. “In the Kurdistan Region, as a part of Iraq, we are a part of this security pact and we no do not want to become a source of threat to our neighbors, whether that is Iran or Turkey.” The message is that by relocating the opposition members, there is no longer a reason for Iranian attacks on Kurds.

What’s actually happening is that your enemies are taking advantage of your weakness, which stems from a lack of unity. Iran has been tightening the screws on Iraq since 2003 and now has the Kurds precisely where it wants them—on their knees—thanks to forced agreements with Baghdad that are subsequently not honored.

Help

Your cousin is calling on the Americans for help, as what’s happening is a result of their involvement from 2003 onward. In response, an anonymous staffer for U.S. President Biden lets it be known that the two largest Kurdish parties must first resolve their own conflicts before accusing the Americans of anything.

And so we come to the core issue: the most important agreements after the civil war were those about power-sharing between the KDP and PUK. These two parties would govern the region together. For every KDP member in the government, there was a PUK member. With the advent of opposition parties, especially in the PUK zone, the PUK lost votes. As a result, that old 50/50 agreement is under pressure. Because the Prime Minister believes that it is no longer justified due to the voting ratios.

The problem is that the KDP would also lose votes to the opposition if internal party pressure were less strong. Because many KDP members also want change but are intimidated or bribed into staying. Abandoning the agreement, however, will lead to KDP’s sole rule and a definitive end to democracy in Kurdistan. Is that what you want, Mr. President?

Ball

Before I left Kurdistan, you were also my Prime Minister and then my President. That’s why I make this appeal. It’s up to you as President to ensure that the Kurdistan Region doesn’t fall back into a green and yellow zone, each with their own governments and even budgets (from Baghdad). Because that would create a snowball effect and give opponents in Baghdad what they want. Do you want to go back to the situation before 2003? It’s up to you to rise above the parties and bring about unity.

Put the ball where it belongs: with the Kurdish politicians. Kurdistan must not be a plaything for Baghdad and its neighbors. It’s up to you to pick up that ball and put it back into play. And to ensure that your people can no longer starve in their land of plenty, of which you are the President.