One hundred years ago, European states signed the Treaty of Lausanne, which partitioned the Ottoman Empire and scattered the Kurds who were part of it across four states. No sovereign state for them, as Kurdish politicians had been promised just a few years earlier in the Treaty of Sèvres. But rather, they became a minority in the remnant state of Turkey and in the similarly arbitrarily drawn countries of Syria, Iraq, and Iran.

The Kurds commemorate this as a sad milestone. All the more because, a century later, they are further than ever from the fulfillment of their dream of independence. In Turkey and Iran, the state wages a real war against the oppressed Kurdish minority, which also has serious repercussions for the semi-autonomous Kurdish regions of Iraq and Syria.

This is particularly evident when the Turkish and Iranian governments need to divert their citizens’ attention from their own failures – which is certainly the case at present. Domestically, they pursue the Kurdish opposition, and in their regions (in Turkey and Iran), they set ablaze vast forest areas.

Increasingly, the two countries also carry out cross-border attacks on their rebellious Kurdish subjects who have sought refuge there. The Kurdistan Region of Iraq, in particular, harbors opposition groups from all three other regions and is therefore constantly under fire.

Attacks

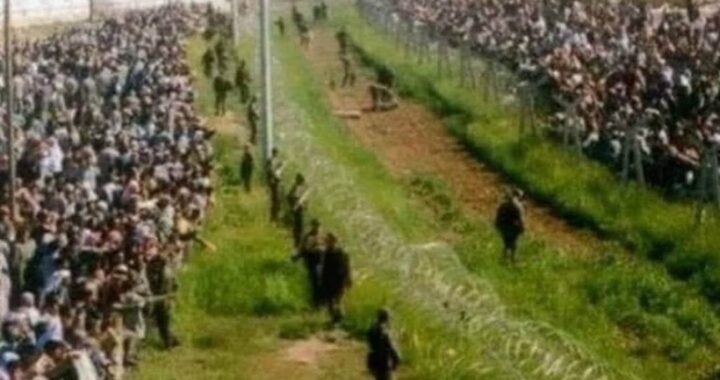

It’s well known that due to Turkish attacks on PKK fighters in the border area between Iraq and Turkey, dozens of Kurdish villages have been depopulated. It resulted in a sort of no-man’s-land being formed. Further along, near the Iranian border, opposition group leaders are also not safe. In the past year, at least five Kurdish activists from Turkey have been killed in the province of Sulaymaniya, and two more from Iran were killed recently.

During the month of June, in the province of Erbil, a new record was reached when the number of Turkish attacks on members of the Turkish-Kurdish resistance group PKK increased by two hundred percent.

In the Kurdish region of Syria, there are also continuous Turkish drone attacks on members of the Kurdish administration and their military, whom Ankara lumps together with the ‘terrorists’ of the PKK.

When I lived in Kurdistan, I would occasionally visit one of the Iranian-Kurdish opposition groups outside Sulaymaniya. The leaders there never walked around their camp without armed guards, always on the lookout for attacks from the Iranian enemy or political opponents. Since Turkey and Iran started using drones, such walks have probably become entirely too dangerous.

A few years ago, I visited the camp of another Iranian opposition group located more centrally in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, which had just been struck by Iranian missiles. Several people had died. Even the group’s positions in the mountains were attacked, as filmmaker Beri Shalmasi experienced up close. More recently, there have been targeted attacks on prominent members of this group. The Iranian Kurds hold the Iranian Revolutionary Guard responsible for these actions.

Disarmament

Diplomatic protests from Baghdad against these military actions on Iraqi soil barely get a response. Iran is now even demanding from Baghdad to disarm these opposition groups by September, or they will launch new attacks. The Iranian opposition should be relocated to special camps and guarded there, according to demands from Tehran.

The Iranians probably have the example of the Iranian resistance group and sect MEK in mind, which operated freely from its bases in Iraq under Saddam Hussein. But after the American invasion, its members were placed in a guarded camp. That later came under the auspices of the UN mission in Iraq. It was ultimately relocated abroad; the MEK now has a camp in Albania.

The internally deeply divided Iraqi Kurds seem to have little to counter this with. Adding to their feeling of powerlessness is the fact that the two largest Iraqi-Kurdish parties each have close ties with one of the two angry neighbors. The KDP is very keen on maintaining good relations with Ankara, and the PUK feels the same about Tehran.

Additionally, their equally divided Peshmerga forces can do nothing to repel the attacks. Only Erbil airport has an air defense system. There, the stationed American troops have been targeted by rockets from pro-Iranian militias.

Air Defense

Now voices in the U.S. Congress are advocating to equip the Peshmerga with air defense weapons. But this requires progress in unifying these forces and bringing them entirely under the Ministry of Peshmerga. The Americans and their European NATO partners have been working on this for some time, a process that encounters resistance. Due to their conflicts and mutual distrust, both the KDP and PUK want to retain control over their own troops.

While the two parties are talking to each other again, they are hardly coming closer together. Thus, the news that finally steps have been taken to set a date for postponed elections and even to restart the Peshmerga unification process, was met with applause from Washington. However, there are Kurdish analysts who label the entire unification process as a farce, which only helps the two parties suppress their own people.

While the Kurds face opposition both externally and internally, it’s noteworthy that for the first time in history, the foreign ministers of both Iraq and Turkey are of Kurdish origin. Dutch Kurd Fuad Hussein is serving his second term in Baghdad; Hakan Fidan was appointed in Ankara in June.

They recently met each other in Azerbaijan. Whether they discussed the precarious position of their people remains unclear. However, considering Fidan’s involvement in secret Turkish peace talks with the PKK and its imprisoned leader Ocalan, and later as the security chief in the attacks on PKK bases in Iraqi Kurdistan, it seems very likely.

Nudge

It is also assumed that he will want to improve Ankara’s relationship with the PUK, in an effort to reduce Iranian influence. Something which Hussein, originally from Khanaqin, just outside the PUK-controlled area of the Kurdistan Region and near the Iranian border, will also be passionate about.

Not that two foreign ministers can solve Iraq and the Kurds’ problems together. But any nudge in the right direction is welcome, given the heavy legacy of Lausanne.