After gas extraction in the Po Delta in northern Italy provides much-needed economic stimulus and increasing prosperity in the 1950s, the country’s artistic cinema also flourishes. In contrast to the unambiguous films about daily routines by Roberto Rossellini and Vittorio De Sica, former art critic Antonioni opts for an extremely visual and subjective style.

He aims to depict the feelings of people who, in a time of financial and economic prosperity, remain ensnared in a web of personal crises, intrigues, and failed relationships. According to Antonioni, society is “dominated by a dichotomy between scientific progress and rigid, stereotypical morality. The result is that humans are heavily burdened with emotional qualities that are not so much old and outdated but rather flawed.”

The embodiment of these nevertheless captivatingly filmed observations is Antonioni’s muse, the actress Monica Vitti. With a single glance, she can convey heart-wrenching despair and bleakness. Her penetrating gaze elevates “L’Avventura” (1960) to ethereal heights. Vitti’s character desperately seeks to compensate for the emptiness in her life through her approach to the fiancé of her mysteriously disappeared friend at the beginning of the film. What follows is a beautifully acted prelude full of doubt and capriciousness.

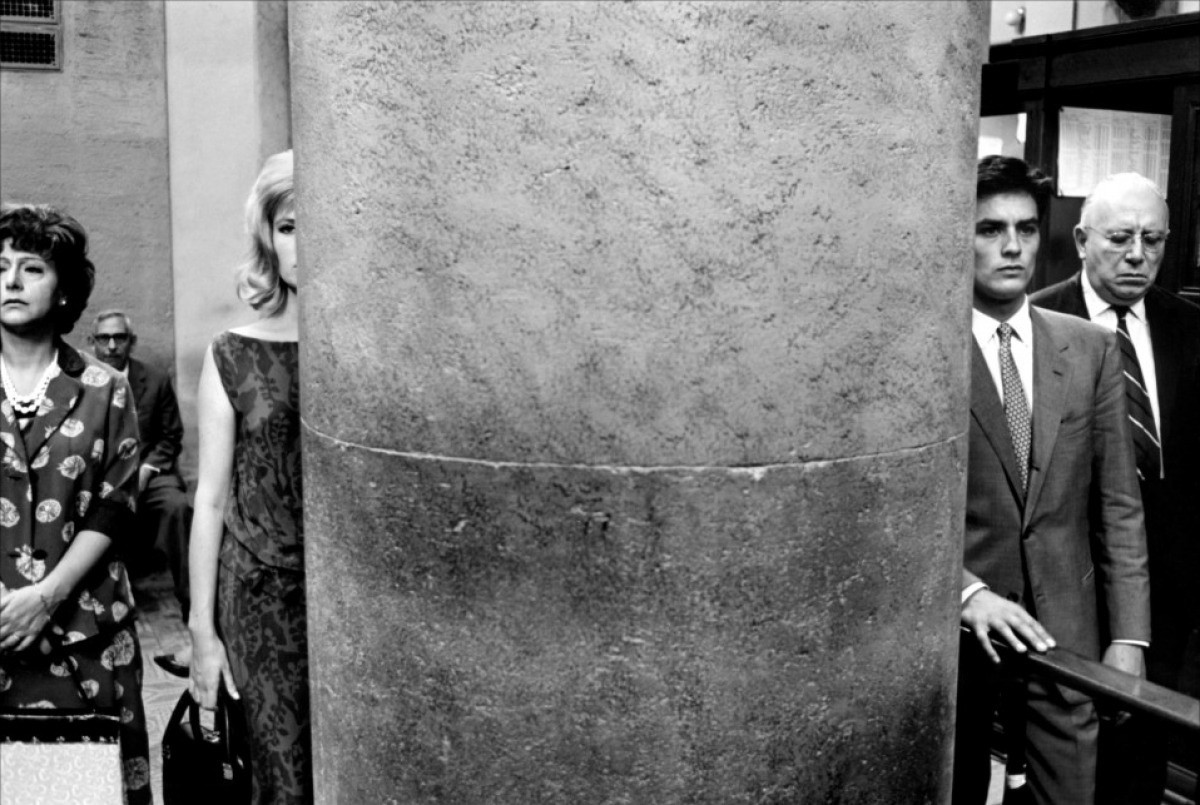

In “La Notte” (1961), someone casually remarks: “every time I try to communicate, love disappears.” And when they do communicate, they often say the opposite of what they mean. Antonioni unabashedly reveals the last remnants of hope and feelings in people who drift aimlessly through life. Metaphors for bitter desolation and despair are shown by the director through the furniture of a room, the emphasis on objects in a strange environment, the foregrounding of architecture, and a landscape in which the characters don’t so much get lost as they lose themselves in it.

Disturbingly, Antonioni is a master of the anticlimax. Usually, everything remains as it is, with little to no change in the lives of people who revolve around each other, talking a lot but saying nothing. We don’t get to see much more, just life as it is, no more and no less, of ordinary people and their loneliness, apathy, and lies. People who are unable to change anything about it, which indirectly leads to an inability to communicate.

An impressive example is “L’Eclisse” (1962). The film opens with one of the most unsettling scenes ever captured on the silver screen. Intuitively, the camera moves through a living room just as two lovers are in the process of ending their relationship. There are silences that uncomfortably linger. What follows is a play of contrasts. Against the backdrop of a city with a modernist feel, encircling love movement takes place between Vitti and her new flame, a young stockbroker played by Alain Delon. Just before the end of the movie, we lose sight of the new lovers without any reason and without prior announcement. They make an appointment they both fail to keep. Suddenly, the film ends with images of anonymous passersby waiting for a bus, illuminated streets, a close-up of a lamppost. The roads look new, almost hermetic, yet there is hardly any traffic.

“Red Desert” (1964) is undoubtedly the most ominous of all Antonioni films. In the opening scenes, a young woman and her son walk through a landscape that screams for immediate environmental activism. The ground appears heavily polluted, with a nearby chemical factory port. Everything here is grim and bleak. However, in Antonioni’s his first color film, characters and the enigmatic nature of the events they encounter blend into meaningful hues and shades. They seem to echo paintings by Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, masters of the absorbed tangible. “If I hadn’t become a director, I would have been an architect or a painter. I prefer showing rather than telling.”

In “Red Desert” we encounter Monica Vitti again. She portrays a young mother traumatized by a car accident. After a suicide attempt, she tries to rebuild her life. Her only anchors are her son and a flirtatious friendship. However, she primarily feels distance and incomprehension from her husband and her surroundings. Her longing for love remains unattainable. Essentially, “Red Desert” is a feature film about personal depression seen from a female perspective.

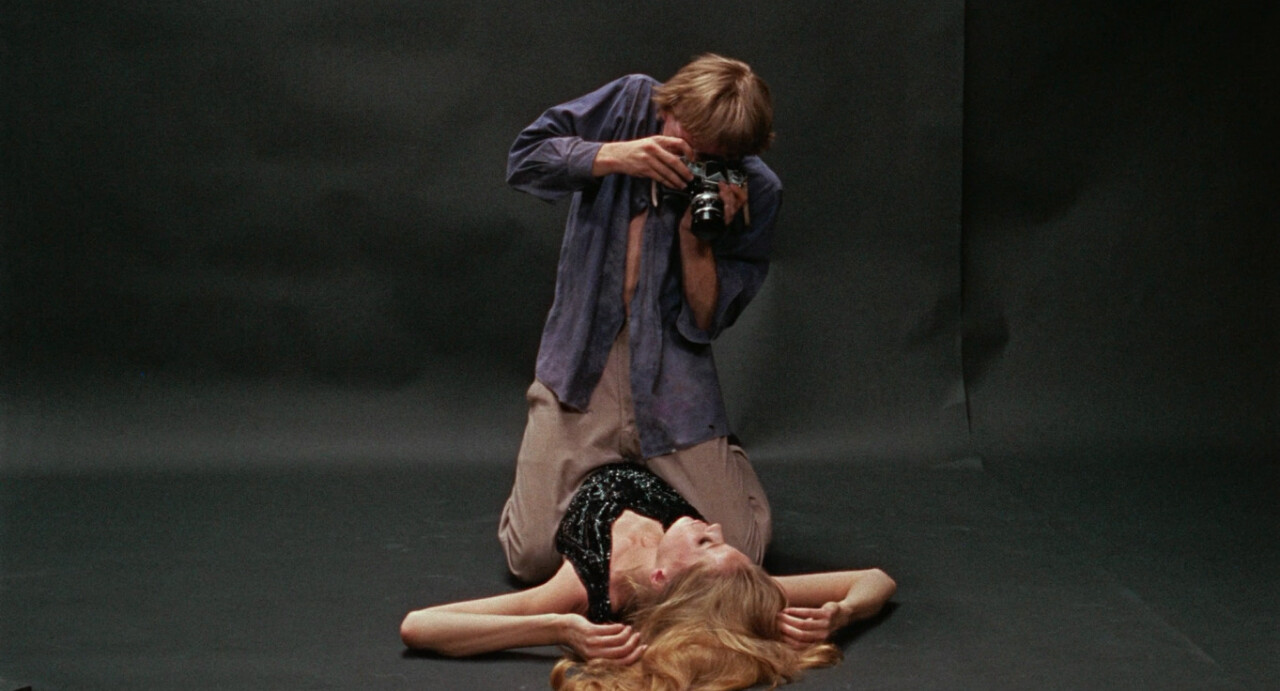

Antonioni’s international breakthrough is of course “Blow-Up”. The hip London of 1966 sets the stage for the life and work of a fashion photographer. By chance, he believes he witnesses a murder in a park. He does find a body, becomes obsessed with it, but the next day discovers that the corpse has disappeared. From that moment on, fixed situations and events are displaced and magnified from their context.

The interpretation of “Blow-Up” balances more than ever between appearance and reality, between the abstract and the emotional. Before the camera zooms in on him during the final scene, the photographer is not only a witness but also briefly a participant in a tennis match for pantomime players. The image evokes primarily emotion and a sense of loneliness. Because who plays a game of tennis without a racket or ball? It is a metaphor for the realization that the photographer hasn’t really progressed much in his life, his work, his feelings.

“It’s crazy how little people’s reactions are to big events when there’s no one around to see them,” says a journalist played by Jack Nicholson in “The Passenger” (1975). At one point, the reporter manages to switch identities, from journalist to arms dealer. But no matter how hard he tries to escape his original existence, actual escape seems impossible.

Chased by acquaintances from his previous life, Nicholson becomes increasingly aware of his past, but also of his renewed false identity. “The Passenger,” also known as “Profession: Reporter”, is pregnant with symbolism, alienation, and detachment. Curiously, the film concludes with a minutes-long, highly peculiar final shot. The camera pans slowly through the window bars of Nicholson’s hotel room, then proceeds uninterrupted around the hotel, ending up back in the same room.

Indeed, the cinema of Michelangelo Antonioni is quite disorienting. Actors walk out of a frame without reason. They are ‘spied on’ as they are filmed from behind. Vigilance is required, as if watching an exciting thriller in which humans are both perpetrator and victim. His images take time to get used to. Getting used to a slow rhythm in which one is thoughtfully immersed in someone else’s existence. Getting used to films where nothing is explained, where solutions and answers are withheld. Indeed, just like in real life.