Interviews with 60-year-old trumpeter Miles Davis are a rarity. No matter how open he appears on stage in recent years, The Prince Of Darkness remains a personality shrouded in mysteries. On the occasion of his new album Tutu, some hoarse words were exchanged via the Transatlantic hotline.

by C. Cornell Evers, OOR, October 18, 1986

Miles is said to be difficult, according to some. Nevertheless, in the extensive interview conducted by Cheryl McCall of the American magazine People a few years ago, he comes across as an extremely likable person: somewhat defiant, perhaps, but with a great sense of humor, self-deprecating, and not averse to self-reflection. McCall painted a somewhat poignant picture of the person behind the musician Davis. A fairly complete picture.

And maybe that’s where we should have left it. Of course, there is still so much more to ask. But whoever is waiting for that, Miles Davis certainly is not. He communicates through his music. Furthermore, over the years, the trumpeter has developed a aversion to the press that displays slightly paranoid tendencies.

Perhaps rightfully so, considering that a legion of primarily jazz critics has never truly ‘forgiven’ him for his ‘collaboration with commercialism’ and his use of ‘cheap sound effects derived from pop music’. They never miss an opportunity to refer to Davis’ classic quintet from the sixties, consisting of drummer Tony Williams, bassist Ron Carter, keyboardist Herbie Hancock, and saxophonist Wayne Shorter. For them, Miles’ ‘betrayal’ begins with the release of the album Bitches Brew in 1970, the legendary record that is seen by pop music lovers, in particular, as the starting point of jazz-rock but was condemned by the entire established order. An identity crisis ensued, and nothing was heard from Davis for five years after 1975.

COMEBACK

In 1981, unexpectedly, the rock-oriented album The Man With The Horn was released, on which Miles plays not only the trumpet but also synthesizer parts. With We Want Miles (’82) and Star People (’83), his comeback was a fact. The master even embarked on a world tour again and performed at the North Sea Jazz Festival in 1984 as part of it. The impression he made there can only be described in superlatives. Miles was back: a superstar reborn.

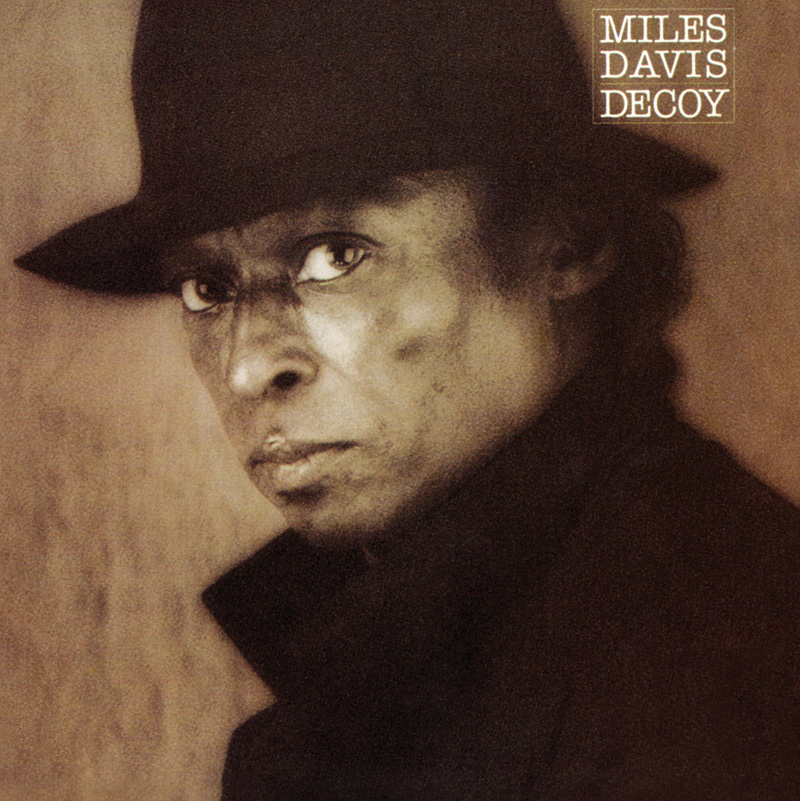

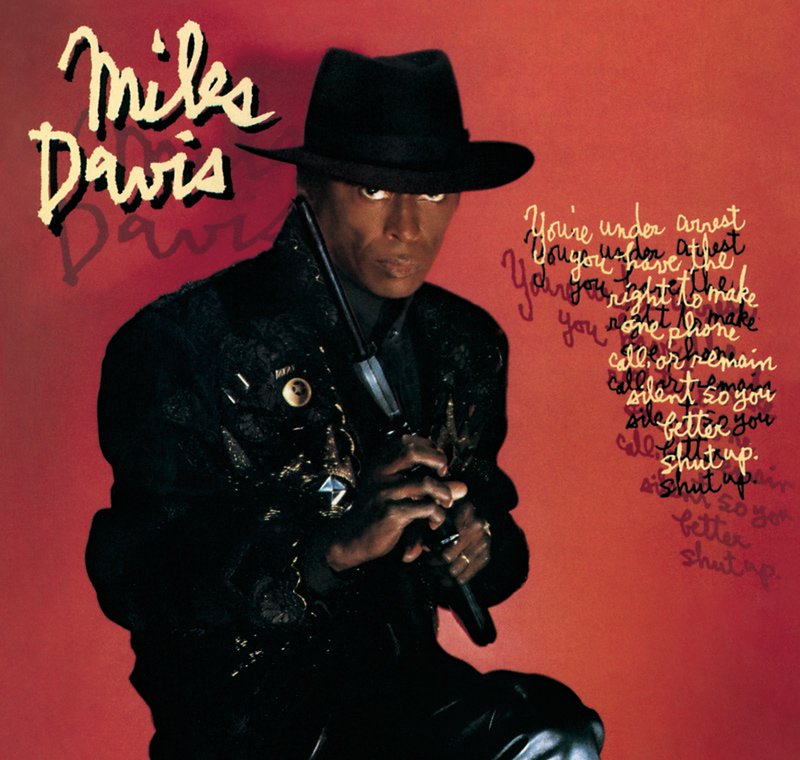

While on Star People, Davis seemed to focus mainly on the combination of rock and jazz, with a strong emphasis on the guitar parts by Mike Stern and John Scofield, on Decoy (’84), the trumpeter unabashedly flirted with funk and pop, a trend that continued on the highly commercial You’re Under Arrest (’85), featuring notable covers and pop songs like Cyndi Lauper’s Time After Time and Michael Jackson’s Human Nature. Even the frontman of The Police, Sting, made a small vocal contribution to You’re Under Arrest and then recruited Miles’ bassist Daryl Jones and saxophonist Branford Marsalis for his own Dream Of The Blue Turtles world tour.

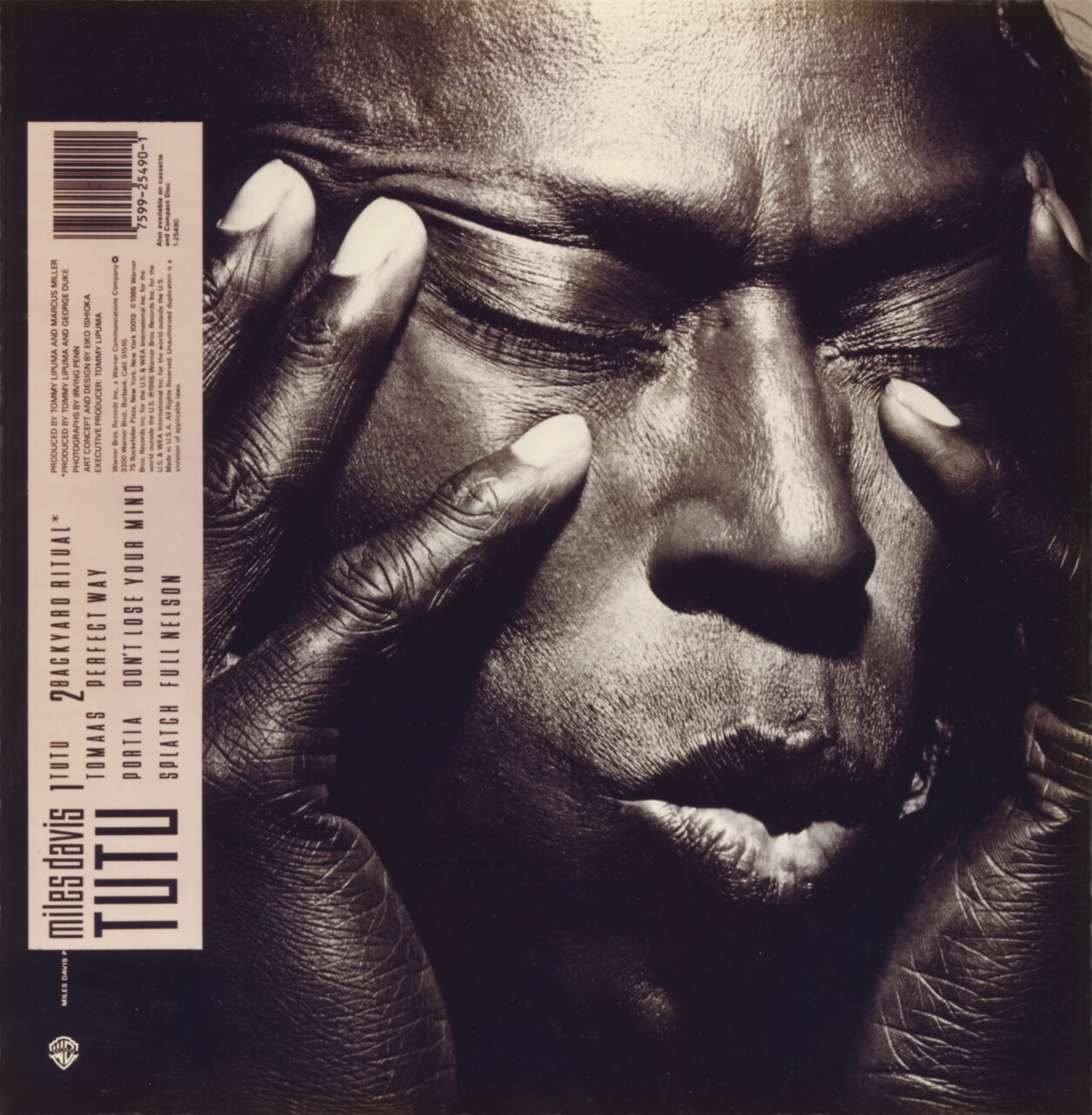

And now we have Tutu, an album for which Miles seems to have given his former bassist Marcus Miller complete creative freedom. Tutu is an album in which, alongside the characteristic sound of Miles’ mostly muted trumpet, synthesizers are abundantly present, supplemented by contributions from Brazilian percussionist Paulinho da Costa and occasionally violinist Michael Urbaniak (Don’t Lose Your Mind), keyboardist George Duke (Backyard Ritual), and drummer Omar Hakim (Tomaas). On Tutu, Miles moves within the trendy funk idiom, as on Decoy and especially You’re Under Arrest, but also manages to give the concept of fusion a very distinct meaning.

THE INTERVIEW

The rules are stringent. The trumpeter only wants to talk to two journalists, and each is allocated twenty minutes. Twenty minutes? Images of Countdown television interviews come to mind, and nerves get the better of me as a representative from the record company tries to establish the connection with New York.

‘Mr. Davis?’ the promo man asks and wants to pass the phone to me. ‘Wait a minute, man, damned, what’s wrong with you?’ comes the retort from the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. ‘Wait until I’m done, not you.’ Shuffling sounds come through. ‘Yeah.’ I introduce myself and ask if we can start. No answer. I repeat my question, and with that hoarse, almost fragile voice, he lets me know he’s ready.

Do you admire Bishop Desmond Tutu?

‘Listen: I only named that album Tutu. Because he has done so much for South Africa… and he is black. The least I could do was to call that record Tutu. I must have admiration for him. Otherwise, I wouldn’t have named that thing Tutu.’

What is the reason that you didn’t record Tutu with a band but left most of it to Marcus Miller?

‘Because we happened to want it that way. It’s easier and more creative. When you work with a bunch of musicians, there are always a few who can only play one style. Music is nothing but style, composed of different styles. When you work with multiple musicians, you have to be patient, wait to see if they will ever be able to play the style you have in mind. But that takes too long, you know. It takes a lot of time and money, especially when you don’t sing. I mean, if you don’t sing, then you have to create your own atmosphere. A singer provides stability. So… you create your own atmosphere… and then the record listeners can create their own atmosphere when they play the record. Do you understand what I mean?’

But still, why Marcus Miller?

‘Why not? From now on, I plan to use composers for my records in that way. So I’ll probably record an album with Herbie (Hancock-CCE), one with Joe Zawinul, one with Prince… I’ll work with composers like Palle Mikkelborg…’

If I’m well-informed, you’ve already worked with Danish composer Palle Mikkelborg.

‘Yes.’

I’m referring to the Auro project for which recordings were made in Copenhagen last year. What can you tell me about this collaboration?

‘Listen, you’re asking the wrong… not the right questions. What happened was that I came across a piece that Palle Mikkelborg had written for the Danish Radio Orchestra. I thought it was very good and recorded it. But when George Butler from Columbia heard it, he came up with the term contemporary jazz. That’s why I didn’t give them the tapes. At CBS, they have no clue about the value of Palle’s work. So… There’s reggae, rock & roll, funky stuff, some free things, ballads, and duets. Five drummers participate, ten keyboard players, singers… That project is one reason why I left Columbia. Because I had to ask The National Endowment Of Arts for money to finish it. CBS didn’t want to.’

You are often accused of catering too much to what the general public wants to hear.

‘I always play what I want to play and do what I want to do. If the audience appreciates what I want to do, fantastic. If not, I’m fine with it too. There are a lot of great musicians who don’t play any instrument. They’re in the audience and know exactly what they like. If I play something that I love a lot, then the audience will love it too. If you can convey your own feelings, if you present it in the right way, it doesn’t matter what it is… or what style. If you present it in the right way, they will love it. Because it’s just a style. That’s how I play music. I play different styles: sad, slow, moody, or whatever you want to call it.’

His reaction to my next question will haunt me for days. The scream contains anger but above all, pain. The question was whether, if he were at the beginning of his career now, say forty years younger, he would play different music, have a different approach. ‘How the hell should I know? Why are you asking me something like that? It’s about what you love and what you want to play. Or what you can play. It doesn’t matter how young you are… or how old.’

Completely devastated by that outburst after indeed a somewhat tactless remark, I decide to dive into pop music. Unfortunately, despite all the rumors, Miles Davis doesn’t listen exceptionally much to the products of this branch on the music tree. ‘I listen to all types of music,’ and when I inquire about his reasons for including a cover of Scritti Politti’s Perfect Way on Tutu, a small storm rages for the second time in a short period.

‘You can keep asking the same thing! That’s what makes me so tired. Because it’s a racist way of asking questions. Now you’re asking about Scritti Politti. Why not George Gershwin? Nobody has ever asked me why I did Porgy And Bess. Or Sketches Of Spain. It’s not about the why. I just wanted to do it. And it has nothing to do with the fact that it’s a young musician and all that bullshit. I don’t know why you’re saying all those things. It makes me angry when someone says those kinds of things. I am a musician and I play what I feel. Whether it’s Stockhausen or Ravel or whatever. When I play Ravel, do they ask me if that man might have been very young when he wrote that particular piece and if that might be the reason why I play it? It’s ridiculous even to think about it! If you were trying to provoke me, well, you succeeded. Nobody asks me those things! Because I don’t know what to say in response. It drives me crazy.’

All I wanted to say is that, in my opinion, it’s an honor for Scritti Politti that you wanted to do one of their songs.

‘It’s a great honor for me to do such a song, to add my arrangements to it. I just hope I did it well and that they won’t say afterwards that I completely messed up that song.’

I love the song as it is now.

‘Thank you. Tell them that when you see them. (milder now) I also did a song for Toto. Everyone forgets about that.’

How likely is it that you will work with Gil Evans again?

‘Whenever Gil wants, I’m ready. He called me and suggested that we do Tosca together. I don’t know when. And I don’t know if it will happen. There’s always the possibility that we start with something and end up with something completely different.’

To come back to Tutu. The record label only credits you as the composer for one song, Tomaas. Most of the material was written by Marcus Miller. Why not more of your own work?

‘I can’t write like Marcus. Many musicians make a big mistake by wanting to write their own material. I recently told that to my son, who also wants to become a musician: “If you go to school to study music, they teach you how to play music by others. And how to interpret the music of others.” That’s what I do. I interpret the music of other people.’

Are there any concrete ideas about a future collaboration with Herbie Hancock?

‘I told him that I wanted to do something with him. He had already written something for me too. But what it is, I can’t tell you. If I reveal everything about myself, there won’t be a damn thing left for me.’ He catches my suppressed chuckle. ‘Ha, you like that, don’t you?’

To briefly move away from music. You played Ivory Jones in an episode of Miami Vice. Can we expect more activities in that direction?

‘I have three or four scripts here.’

What kind?

‘Well, back to the same subject again. Every role that comes my way, they always want me to play a pimp. Goddamned! What I want to see is a script about what I do and what I want to say. About my lifestyle. But every time, they damn well want to see me as a pimp. Not all pimps are black.’

Have you seen the film Round Midnight by Bertrand Tavernier, dedicated to, among others, Lester Young and starring Dexter Gordon?

‘Some parts.’

Did you like it?

‘Sure. Dexter is very natural. But if you’re black, you have to act your whole life. We have to be able to put on different faces, have a built-in radar system that warns us as soon as there are prejudices… I’m used to living with that burden.’

Would you be willing to play yourself in a film?

‘Certainly. But that’s not possible. So I’ll write a book.’

If you had the opportunity to work with the same quartet that accompanied Sting on his solo album, what would you do with them?

‘I would do what I do. But I wouldn’t use them like Sting. Sting used them. He didn’t let them do what they’re capable of.’

You used to differentiate between making music and entertainment.

‘It’s the same for me. If you love a piece and the audience does too, then you feel the vibrations. Then you’re entertaining by playing. When I play, I compose the pieces anew every time. Every evening is different. It’s not like one man wrote the songs. Marcus wrote the framework and we fill in the compositions. And that can be faster or slower. In Brazil, we play fast, while in Germany the band plays very slow. Germans show much less whether they like the music than Brazilians do. The band could feel that very well when they had to perform in Cologne after Brazil. The feeling while playing remains the same, but the way it’s expressed changes, you know, um… what was your name again?’

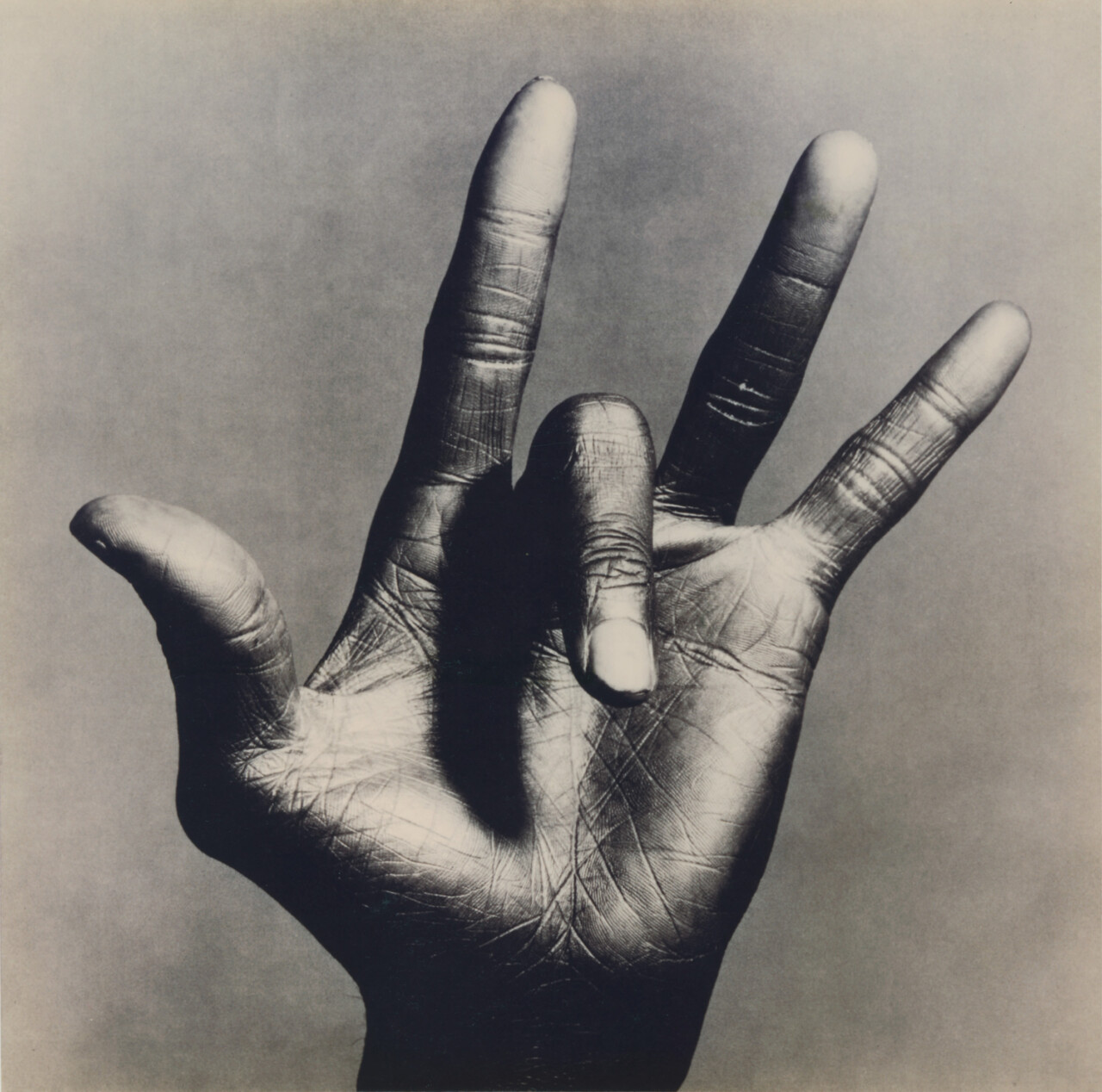

THE HAND

The album Tutu is housed in a beautifully designed cover by Japanese Eiko Ishioka, featuring stunning close-up photos of Davis on both the front and back, taken by photographer Irving Penn. But it’s the inner sleeve that catches the eye, with a photo of a curved trumpet hand, lined with chipped nails.

‘That’s my hand, yes. Eiko chose that photo. Eiko is a friend of mine and she was fascinated by Penn’s work. I love the way she thinks. She says my hand looks very religious.’

It’s a hand that portrays a life story.

‘Do you mean my lifelines?’

No. I see the hand of a man who lived his life the way he wanted.

‘That’s Eiko. She sees things. She knows things. She’s amazing. If you ever meet her or Irving Penn, you should definitely tell them how much you admire them.’

TEN MINUTES

Just as I feel that the conversation is taking a completely different turn and Miles is being kind and accommodating, I receive a signal from the office that my time is up. However, the trumpeter protests. ‘I’m just getting started. You’re supposed to be like a bloodhound on my trail, and now you want to end it already!’

Would you like to continue talking then?

‘Of course.’

You know there’s another journalist waiting?

‘They’ll ask the same things as you. Let them wait. I want to keep talking. Ten minutes. Okay? Go ahead.’

There were rumors that Prince would be involved in the follow-up to You’re Under Arrest. However, on Tutu, Prince is not among the featured artists. Were there any issues?

‘No issues, no. He wrote me a letter and sent two tapes. One contained a fully finished song that I could use, with or without vocals, whatever I preferred. The other tape had snippets of a composition. After he heard things we had already done, he withdrew everything. He didn’t think his own material was good enough and said we should go to the studio together, just the two of us, with the door locked. I can appreciate that.’

Another desire of yours would be to collaborate with Frank Sinatra.

‘I don’t know anything about that. I haven’t heard anything either. I prefer to listen to Frank, you know. I once said something similar to him as I did to Duke Ellington: “I’d rather listen to you than play with your band.” That was in 1949. Besides, I was still working on Birth Of The Cool back then. One of Frank’s people asked me a while ago. But Frank doesn’t need me. As a boy, I listened to him, sang Night And Day and such, and learned how to phrase from him. And from Orson Welles, who also had an exceptional way of phrasing. Kind of like those rap guys do now.’

Have you followed those developments?

‘I knew that would happen. The Last Poets. Because that’s how the Black Panthers… rap comes from there. And now I have to go. The ten minutes are up.’

Twenty-three minutes with Miles Davis. They leave a temporarily indelible impression.

WWW

milesdavis.com